It is well established at the time of writing this article in July/August 2020 that the effects of the Novel Coronavirus on the world are significant. We are likely to feel the effects for some time to come. In the main, those governments who have not stuck their heads in the sand have reacted in two major ways:

(1) They have tried to isolate citizens to reduce the speed at which the disease is transmitted, by curbing access to public life, and in doing so, closing or restricting the operation of many business; and

(2) They have introduced financial stimuli to try to offset the impact of the business closure on the economy

The medium and long term prognosis for the pandemic and its effect on the global economy is not yet clear but what does appear clear is that the effects will be felt for some time.

These measures come at significant cost so I wanted to look at how this could be recouped by looking at some examples of the interplay with taxation.

As I set out to write this article I had a clear concept in mind. I wanted to show that the data collected by governments under Common Reporting Standard (or FATCA in the case of the US) could potentially be used to model the impact of any new taxes introduced on foreign-held assets and investments. However, the more I researched, the more intrigued I became in the economics involved, and eventually got so caught up in the detail that I had to step back a little. I found looking into the economics of Wealth and Inheritance taxes so interesting I realise I need to write a separate article on that in future to do it justice, and also to stand a chance of finalising this article at any time in the near future! So, this article does talk about what I originally set out to discuss, but it also considers the various ways governments might consider tinkering with taxation as a way to pay their corona bill.

Readers may recall from my first blog how important context is to me. I don’t think it’s helpful to talk in the abstract about financial concepts. It’s difficult to relate, so I’ve found some concrete examples of the immediate financial consequences on governments in their COVID intervention plans and we can take it from there. Being British, living in Switzerland, I’ve gravitated towards some examples based on those two countries but I hope to address the situation more generally, using international data from the OECD and the European Union.

The immediate cost of coronavirus to governments

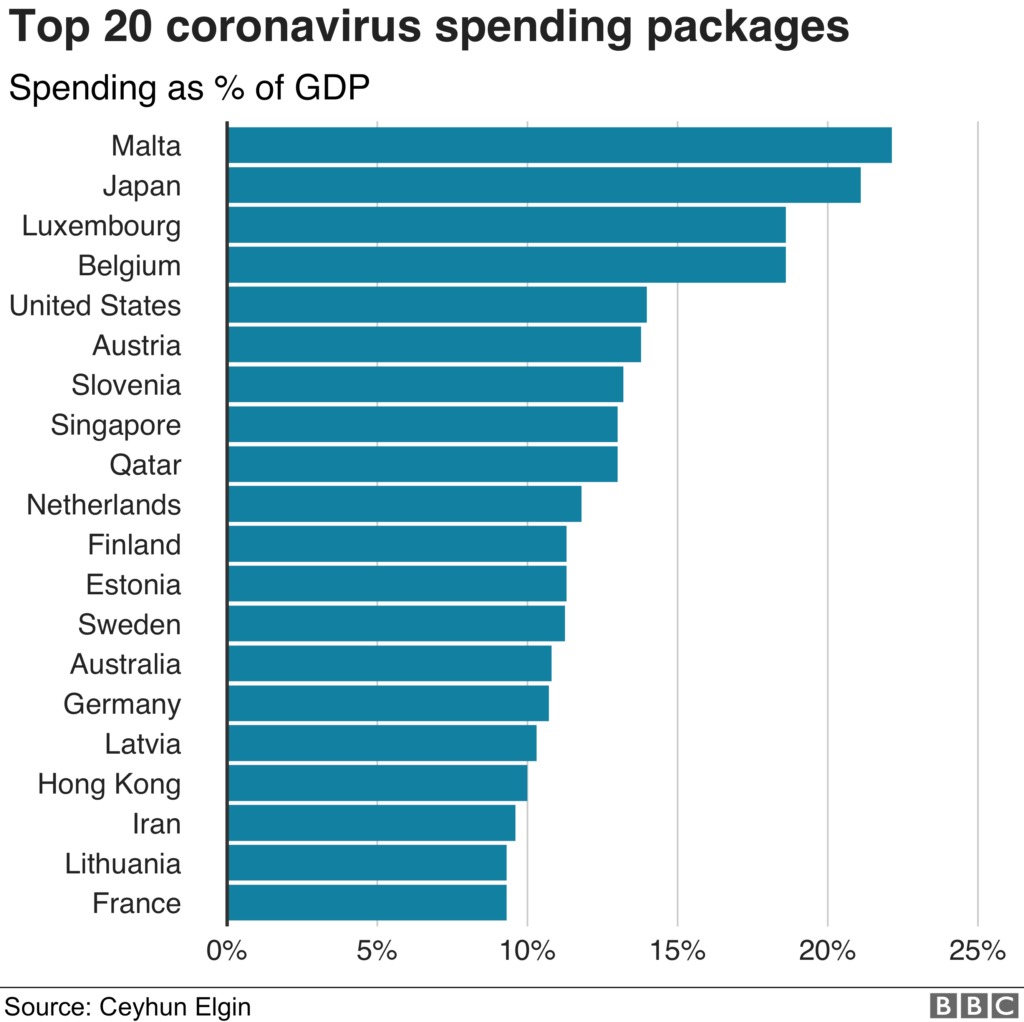

The BBC, back in May, published an article (the graphic which I’ve reproduced on the right) with some statistics that make a good starting point. In essence, many governments have committed somewhere between 10-20% of their Gross Domestic Product (GDP, which is the total economic output of a country in a year) to economic relief efforts. Some a little more, some a little less, and some indirect funding is harder to quantify, but this at least gives us a reference point as to the basic cost.

I struggle sometimes to identify with GDP figures – I just can’t relate to them because they seem to abstract for me to understand what they mean – so to help put some meat on the bone, let’s look at the concrete example of Switzerland’s efforts.

Switzerland’s fine

According to an article published on SwissInfo.ch Switzerland has budgeted approximately CHF 65bn (which accounts for about 10% of GDP). Helpfully, they’ve already explained in the same article how they anticipate covering the cost of this – Switzerland already has high levels of liquidity and has expressly stated that they do not intend to levy new taxes to cover the cost. Good for me, as a Swiss taxpayer!

How will other governments pay for it?

Let’s assume our model of around 10-20% of GDP is our starting point, and see how much that money amounts to in the context of overall government spending, to see how much we’re talking about.

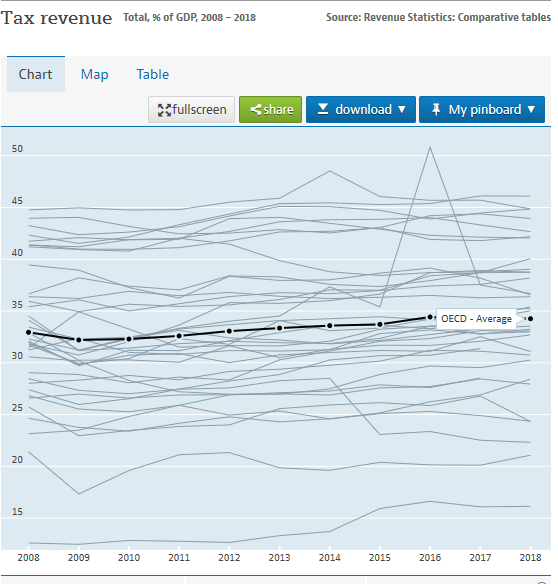

Helpfully, there are a number of publicly available data sources to find out more about government spending and taxing habits. One of these is the OECD statistics website which contains an astonishing wealth of information including breakdowns of exactly which taxes in which countries produce how much revenue, measured either in thousands of million US dollars or as a percentage of GDP.

My inner geek got quite carried away delving into the detail available on this site but I acknowledge I might be a little “special” as my Mum used to like to call it.

GDP is quite a helpful guide if we’re comparing with COVID spending but I like dollar amounts too. They help me understand how much we’re talking about.

Looking at the total tax revenues for all the countries listed in the OECD resource, the 2018 figures suggest that gross tax receipts tend to vary between about 15% and 45% of GDP, averaging at around 34%.

So let’s consider this. In an “average” country, spending 15% of its GDP on COVID measures, that’s just over half of its normal annual tax revenue (or let’s assume that taxes are roughly equivalent to the cost of running the country and say the government could only cover this cost if it did pretty much nothing else in the year and cancelled most of its public services. Clearly not an option). To put it another way, if a government wanted to get its money back over the next, say, 5 years, it would need to increase taxation by some significant measure to recoup their investment.

Example: Switzerland (who has said they won’t raise extra taxes, but it’s a useful example):

To take a concrete hypothetical example based on real numbers, to make things more tangible, let’s apply this to the economics of Switzerland and work through the numbers. Based on figures available in this interest official guide from the Swiss government to the Swiss tax system, the total tax revenue for 2016 at all levels of government was CHF 138bn (only CHF 63.9bn of which was levied at federal level).

Compare this with the budgeted cost of COVID measures: CHF 65bn (!)

If we compare this outflow with the income the government generate, this is 47% of the total tax revenue by all levels of government in one year. If the Swiss wanted to pay this down over a 5 year period (unlikely) by raising additional taxes, they would need to generate additional tax revenue of CHF13bn per year.

So taxes would need to go up by 9.42% (CHF 13bn increase / CHF 138bn tax base) and the country would have to hope that the economy can support such a drastic additional tax drag. This all seems like an unlikely scenario, and, as I’ve mentioned before, the Swiss have stated publicly they don’t want to raise a new tax to cover the cost. I just thought it was a useful way to demonstrate the scale of the financial burden we’re talking about, and how it relates to the tax take of a country.

Based on the above assumptions, governments will generally have to consider (1) taking a long term view on the covering the cost of their COVID measures and (2) think quite carefully about whether they want to introduce new taxes, cut other spending, simply assume new debt and hope the economic recovery provides a natural resource to absorb much of this cost.

Most likely the money won’t magically appear on its own, and the prospect of adding to existing crippling long term national debt is unappealing.

Other governments may have to try harder to cover the debt they incurred. Whilst an economic recovery will eventually naturally contribute to higher tax revenues, many governments will be considering whether they should increase taxes to recoup the money they paid out.

There was speculation last month that the UK might introduce a wealth tax to cover the cost, but this was downplayed by the UK government as something they wouldn’t do.

What new or additional taxes could governments introduce?

I think here it’s helpful to consider what the main tax generators are, to see what changes governments can actually make to try and increase the amount coming in.

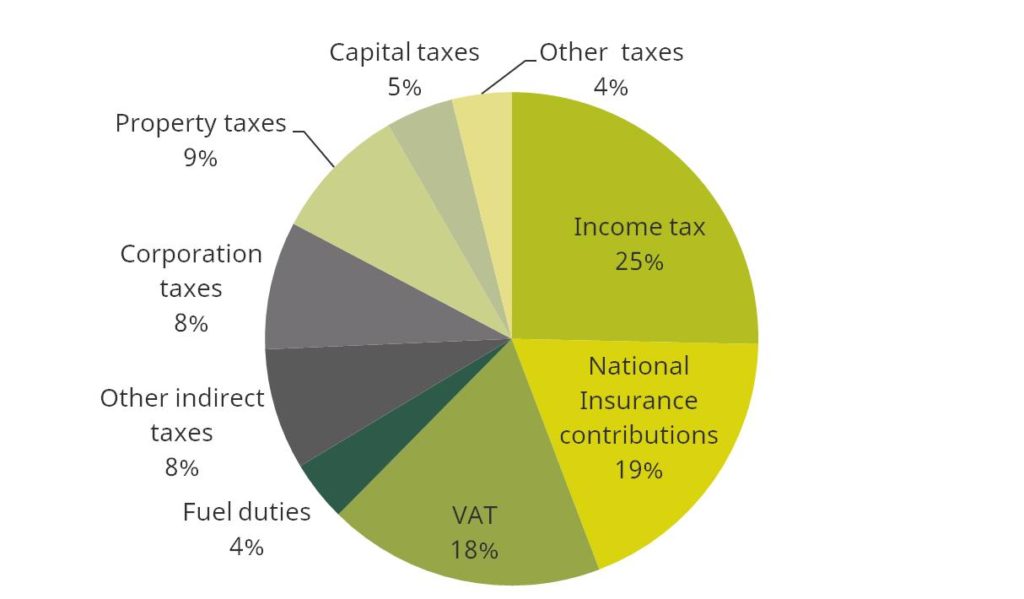

The OECD has a mountain of data setting out the tax revenues of each member country by type and sub-type, set out in USD or % of GDP but the information there is so comprehensive that it’s difficult to work with so I’ve taken this chart from the European Union as a representative indication of where the big ticket tax items are. This is taken from the EU’s Eurostate website, which can be accessed here.

Naturally, with tax policy being a very domestic affair, driven by politics, each country has their own unique mix, but interestingly, a major driver is duties on products (like alcohol, tobacco and petrol), sales tax and import tax. Any change to this would make a bigger difference to the tax take, but, if you’re trying to increase consumption and restart an ailing economy, it might not be politically acceptable to increase taxation on this if you’re trying to encourage people to spend.

Example: UK

In the UK the split is as follows, and being able to focus on a single country for a moment allows us to look in a little more detail at the main taxes. The table here is taken from the Institute for Fiscal Studies 2017 publication “Tax Revenues: where does the money come from and what are the next government’s challenges”:

Here, sales tax (VAT) and fuel duties together make up 22% of total taxation. Income tax (25%) and social security contributions (19%) are also important sources of tax, with corporation tax at a modest 8% of all revenue collections.

In the UK, social contributions (National Insurance) are (to my surprise when researching this article) are actually ringfenced to pay for social benefits, the health system and retirement pensions. Also, this is mainly derived from employment income so it is politically tricky, and I probably wouldn’t mess with this essentially standalone dynamic to try and recover the costs of fighting Coronavirus.

Which is the right tax to adjust or bring in?

How to find the right balance? Just increasing tax rates across the board is not ideal or realistic. It needs a targeted approach and governments will need to consider who can afford to pay any new or additional taxes. They may also need to consider politically palatable options?

Corporation Taxes

With the exception of a few very large, stable and profitable companies, most corporations have struggled through the Corona times. Either they are further up the supply chain and have no way to drive the demand of their corporate customers, or they have suffered a lack of customers due to lockdown. Either way, they are struggling. Increasing corporation taxation, whilst tempting, will probably not yield positive results. Firstly, profits are under pressure so will an increase in taxation lead to an increase in revenues? Probably not for a few years. Secondly, and apologies for stating the obvious, companies generally employ people and, increasing the tax burden on employers could make Corona more expensive for the country as a whole by driving towards job losses, at a time when governments need to be supporting commerce.

Sales Tax / Import Taxes and Duties

This is actually a big ticket item in a number of countries! However, for the same reason I wouldn’t increase corporation tax at the moment, adding to the cost of sales at a time that governments are encouraging people to spend seems a little short sighted. However, import tax increases, if feasible, could appear to generate revenue at the cost of foreign businesses and therefore be a politically acceptable way of bringing in more taxes. However, the world is ever more interconnected, so two big things could go wrong here: (1) retaliatory charges by foreign governments (China vs US, anyone?) and (2) so many domestic business may be relying on foreign-produced parts to actually be able to make or service their own products, so on balance, it probably looks like a better idea in abstract than it is likely to be in practice.

Personal Income Tax

The OECD suggests that Income Taxation is generally the most effective generator of taxes. Depending on the country, this generates between 25% and 40% of overall revenues in OECD member states (with the notable exception of Denmark, which derives more than 50% of its tax from income tax). A well-targeted income tax increase might bring some improvements, but for the same reasons set out above, the better way might be to refrain from changes that would hit employment income.

Some kind of tax on savings and capital gains might be a viable measure.

Wealth Taxes

There was some talk in the UK about introducing a possible wealth tax to help cover the cost. Certainly the UK Labour (opposition) party shadow chancellor and former cabinet secretary Lord O’Donnell thought it would be a good idea. Maybe it is. This would probably put the burden on the shoulders of the section of society that can afford to help pay, but OECD data suggests that those few countries that levy a wealth tax only bring in about 0.2% of GDP with this charge.

The UK government have denied they will introduce such a tax but even if they did, and they levied something reasonable that was comparable with existing wealth taxes in other countries, it would make such a small difference to the economics involved, I wonder if it really makes sense.

The UK already has an inheritance tax which yields approximately 0.2% of GDP. In 2020/2021 the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) expects such a small impact that they didn’t even bother listing it separately.

The UK’s GDP based on the 30 June 2020 figure published by the ONS is £512.5 billion (that’s about USD 670 billion).

Basically, using the GDP amount, and assuming average revenues of 0.2% of GDP, it would produce around GBP 1 bn.

This is clearly not nothing, by any stretch, but figures announced by the UK government in July 2020 suggest the overall cost for the UK this tax year will be £300bn according to this BBC article. Adding a new wealth tax may well help, but it’ll take 300 years to offset the cost, so it’s no silver bullet, by any means. I don’t think just introducing a generic wealth tax, even if the government stood behind it, would cut the mustard, quite frankly.

You could, of course, go somewhat further as suggested by a Guardian columnist and apparently the Institute for Fiscal Studies and go for a one-off larger charge of 10% on private wealth but this smacks of confiscation and it might not go down well. Where exactly the dividing line is between taxation and asset confiscation might sometimes be difficult to see, and will be subjective, but I think 10% is on the confiscatory side.

Some other countries already have a wealth tax, most don’t, but it’s a drop in the water and won’t pay the bills on its own, if kept to moderate levels.

One factor of taxes charged on the moderately wealthy is that a lot of money is tied up in tangible assets so a badly targeted wealth tax could cause cashflow problems. This could be remedied by focusing on bankable assets, and/or only charging such a tax on higher wealth segments, a bit like the US does with its federal inheritance tax (2020 tax only applies to individual estates over USD 11.58m, and couples with combined wealth of USD 23.6m), but governments would need to consider all the consequences – charge at too low a level and it will be more of an irritant than a revenue-raiser. Charge at too high a level and people may start to relocate to countries with lower tax rates, eroding the taxpayer base (example: France).

One-off Assets Tax

Of course, it doesn’t just have to be the country of residence that generates a new charge, at a pinch you could just create a one-off on assets custodised or managed in your jurisdiction like Cyprus did (attempted) in the last financial crisis, but you’d need to be pretty confident that you didn’t destroy your credibility as a financial centre, for fear of endangering the industry, and in turn jobs, both of which provide employment as well as direct and indirect and tax revenues on an ongoing basis.

Modelling data on CRS information?

So let’s say you’ve decided a package of measures combining revenues from corporates doing business in your country, as well as people who hold liquid funds overseas – is there a way you could predict how much revenue a new or increased taxation on these assets could generate, before you even enact the new tax rule?

What if you could model the impact based on data of overseas accounts? People who hold money overseas rarely generate much sympathy with voters, and the information is already being exanged between governments in the form of CRS.

CRS already reports the following information on overseas financial accounts held by tax residents to their home jurisdiction:

- Income/Gains

- Balance as at year end

Imagine if you were considering a new basis for taxation of income, wealth or gains, and you realised you could model a new tax base on this information about foreign accounts, combined with whatever information is already available about domestic accounts.

A word of warning here: Using the CRS information in this way is not in line with the basis on which it was provided under the relevant tax information exchange agreement or Double Tax Treaty, the model text for which states: “The Parties shall provide assistance through exchange of information that is foreseeably relevant to the administration and enforcement of the domestic laws of the Parties concerning the taxes covered by this Agreement, including information that is foreseeably relevant to the determination, assessment, enforcement or collection of tax with respect to persons subject to such taxes, or to the investigation of tax matters or the prosecution of criminal tax matters in relation to such persons.”

However, if you had the data, and the ability to use it for this, it would be tempting, wouldn’t it??

Another proviso to mention is that much of the data will be misleading. A whole number of rules that may involve duplicated reporting due to classification mismatches or quirks of the way CRS work, so as a government you would need to be careful not to assume these are too representative. After all, an information reporting regime shouldn’t be confused with tax reporting:

- Joint account holders will be reported twice

- Some people (settlors of some trusts, some protectors and some beneficiaries) will be attributed values they don’t own and can’t be taxed on.

- People who didn’t fix an indicia will be reported in two countries

So, it might be tempting to use the CRS information to model new tax moves to cover the cost of Corona measures, but it wouldn’t be appropriate.

Are there any crazy ideas out of left field that could be considered?

New taxes on international tech firms

Governments could target international online traders/advertising revenue/corporate international planning (Google etc, Starbucks) – this is generally good sport for politicians.

Let’s face it, Facebook, Google, Amazon and Apple are doing rather well for themselves, have record-breaking revenues, huge levels of accumulated share capital and are regularly lambasted for not paying their fair share of taxes through clever structuring. These are companies that governments could certainly try to tax without causing re-election problems.

New taxes would need careful design. Also, all these companies are headquartered in the US, whose government can be a little protective with retaliatory action.

European countries have recently tabled a “Digital Services Tax”. A study by Copenhagen Economics suggests that the potential tax yield of the proposed EU Digital Services Tax, which was tabled to cover exactly this problem, could generate EUR 3-5bn for European economies (although this would be watered down once you start splitting it between the various taxing governments). This would be a targeted tax on specific segments of specific markets which are arguably not paying a fair level of taxation in the countries they sell their services in. More information on the current status of this proposal is available here: https://taxfoundation.org/digital-tax-europe-2020/

Increased (creative?) enforcement attempts on existing measures

The European Union can get a little upset about tax deals agreed by its member states to attract business. For example, Apple had a well publicised tax deal with Irish. The EU ruled in 2016 that Apple had to pay EUR 13bn in back taxes to the Irish government but this was just successfully appealed in EU courts (with a final appeal to ECJ still open). Governments could look along these lines for opportunities to fill their coffers, but it would deter companies from doing business with them again, at a net cost to employment and tax revenue. And they will have to invest a lot in legal battles which they may not lose. On balance, probably not a great move unless you’re desperate.

Go after those naughty foreign banks…

The 2000s have seen a lot of governments aggressively pursuing banks for large one-off large payments for assisting citizens in committing tax evasion (e.g. France vs UBS, US versus pretty much every Swiss bank) but that’s just a one-shot policy and it’s been overused by Germany, the US and France recently. However, it seems to have been a successful strategy.

Targeted “temporary” taxes

One idea might be to introduce a tax (possibly one of the ones discussed above, or a variation on a theme) that is in place for a short period of time, expressly for the purpose of covering a particular cost. The Germans did this in 1991 with their solidarity tax to assist East German regions with infrastructure projects. Perhaps the risk with temporary taxes like this is that they can sometimes be forgotten by government. In Germany, this tax is still being charged 30 years later, although suggestions are now being made that this should be addressed now it’s not needed for the purpose it was established for. Good job someone finally remembered!

Closing comments

On balance, to successfully cover the cost of Coronavirus, countries probably need a combination of measures and will need to take a long view, balancing deferral (loans) with long term economic growth, but let’s hope countries don’t play chicken with each other on tax policy.

On the bright side, a group of wealthy individuals have just written an open letter basically begging to be taxed https://www.millionairesforhumanity.com/. I find it laudable that they step forward. Unfortunately, they all live in different countries and it may not be immediately clear what taxes should be introduced, but look on the bright side: At least they’ve offered, and maybe this is a place to start?

Thanks for reading!

PhilG

Thank you, next please!

If you’re worried about missing the next article, please let me have your details and you can be one of the first to find out!

The mailing list is hosted on Mailchimp and only used for sending new article alerts. You can unsubscribe at any time.